Albert and Flora Lewis, with Warnie

Photo courtesy of C.S. Lewis: Images of His World – Douglas Gilbert and Clyde S. Kilby

Text Key:

CL – Collected Letters

AMR – All My Road Before Me

SBJ – Surprised by Joy

LP – Lewis Papers

There are many biographies detailing the young life of C.S. Lewis. The general impression is that he was particularly close to his mother, but she passed away of cancer when Lewis was only nine. Also widely acknowledged is that Jack Lewis had a contentious relationship with his father. In today’s post, we will examine the Collected Letters, as well as other various texts, to explore these individuals in greater detail. The life of Flora Lewis was the inaugural post for my Women and Lewis series (in 2013) which you can read here. Today’s post will include more general information about Flora. For more specific reading on how Flora influenced Jack, check out the chapter that I contributed to the book Women and C.S. Lewis.

FLORA LEWIS

Florence “Flora” Lewis was a woman before her time. While many of her friends were starting families, Flora instead chose to attend college at the Methodist College in Belfast, as well as Queen’s University (then Royal University). She achieved first class honors in Geometry and Algebra in 1881. In 1885, she earned first class honors once again in Logic and second class honors in Mathematics. She earned her B.A. degree in 1886, one of small selection of women who were not only college-educated, but earned degrees in a field deprived of females. Flora had already denied the proposal of Albert’s brother when Albert began to approach her about a relationship. However, Flora denied his advances also, saying she only sought him for “friendship.” Albert then altered his approach, exchanging letters about the works of John Ruskin and other authors, highlighting their mutual love for good literature. Flora’s short story, “The Princess Rosetta” was published in The Home Journal in 1890 (no copies survive). Albert wrote asking for a copy. Flora reluctantly sent it to him, figuring that he was too accomplished a man to think much of her writing. To her great surprise, Albert responded with nothing but high praise, extolling the work for its brilliance. Flora eventually warmed to Albert, and the two married in 1894. Warren was born in 1895; Jack followed in 1898. Flora was the daughter of clergyman Thomas Hamilton, who served at St. Mark’s Dundela in Belfast (after serving four years in a church in Rome). The Lewis brothers attended this parish as children, and later, installed stained glass windows there honoring their father and mother. To view these beautiful memorials, please visit St. Mark’s website here and click on “Photo Gallery.”

Flora was so used to the ecclesiastical life that church learning was second nature. Interestingly enough, Flora believed that she was among the “least favorite” of the four Hamilton children, and perhaps this is why she refused to take a “traditional route,” refusing to adhere to her parents’ (and society’s) expectations. Warnie admits that his grandfather Hamilton utilized “outworn literary cliches” and possessed “intense religious bigotry” for Catholics as seen in some protestant circles in late 1800s Belfast (Flora Hamilton and ‘A Miracle at Firenze’ – Journal of Inkling Studies). In Volume 1 of the Collected Letters, Walter Hooper includes a piece by Flora titled “Modern Sermon,” which is essentially a parody of a sermon written in 1892 satirizing the curate Mr. Palmer (or perhaps, Hooper suggests, her own father):

“‘Old Mother Hubbard, she went to the cupboard

To get her poor dog a bone.

But when she got there, the cupboard was bare,

And so the poor dog got none.’

“Mother Hubbard, you see, was old; there being no mention of others, we may presume she was a lone, a widow – a friendless, old, solitary widow. Yet did she despair? Did she sit down and weep, or read a novel, or wring her hands? No. She went to the cupboard, and here observe, she WENT to the cupboard, she did not hop or skip or run or jump, or use any other peripatetic artifice; she solely and merely WENT to the cupboard.

“We have seen that she was old and lonely, and we now see that she was poor. For, mark, the words, THE cupboard; not ‘one of the cupboards,’ or the ‘right hand cupboard’ or the ‘left hand cupboard’ or the one above or the one below, but just THE cupboard. The one humble little cupboard the poor widow possessed. And why did she go to the cupboard? Was it to bring forth golden goblets or glittering precious stones, or costly apparel, or feast on any other attributes of wealth? IT WAS TO GET HER POOR DOG A BONE. Not only was the widow poor, but the dog, the sole prop of her age, was poor too. We can imagine the scene. The poor dog, crouching in the corner, looking wistfully at the solitary cupboard, and the widow going to the cupboard in hope, in expectation…” (CL, 1009-1010)

Flora and Albert had a happy marriage. Jack writes in Surprised by Joy that he had “good parents.” Flora often took her children to the sea to escape the damp Belfast climate. She would encourage them to be curious, to strongly develop their intellects by teaching Latin and French, as well as teaching them to play chess. Warren Lewis writes that these trips were “the highlight of our year” yet they were rarely joined by their father: “Urgent business was his excuse – he was a solicitor…I never met a man more wedded to a dull routine, or less capable of extracting enjoyment from life…I can still see him on his occasional visits to the seaside, walking moodily up and down the beach, hands in trouser pockets, eyes on the ground, every now and then giving a heartrending yawn and pulling out his watch” (Letters of C.S. Lewis, 16).

Yet Flora often begged Albert to join them by the sea. Below is a letter published in C.S. Lewis and the Island of His Birth by Sandy Smith, a prominent Lewis scholar residing in Belfast:

“Quay Road [Ballycastle]

16 August 1900

My dearest Bear

I am sorry you are not coming down this week, but of course it is much better to wait till the middle of the week and have more time with us; remember Thursday will be the 23rd [Albert’s birthday]. you must try to get down for that…Babsie [Jack] is not sleeping very well the last few nights; he is not cross, but wants to get up and talk and play. I suppose it is the heat. He talks about his pappy and wants to go and meet him when he goes out…Always your loving wife, Flora” (101)

Jack as a baby

As many know, Flora would later develop abdominal cancer. Her first surgery in February of 1908 was performed on the dinner table at Little Lea. Flora had been sick with headaches and had become exceptionally weak for some time. Jack remembers having a toothache and that he was told his mother “couldn’t come” to him (this was not necessarily during the surgery, but during the darkest depths of her illness). Flora rallied for a few months, but the second surgery revealed that the cancer had worsened. Albert lovingly attended her sickbed. Her final words, in response to a comment on the goodness of God were, “What have we done for Him?” Flora died on Albert’s birthday – 23 August 1908.

Lewis compares Flora’s death to the “sinking of Atlantis.” All of his childhood innocence was stripped away in an instant, and the trio of men were left to inhabit Little Lea. Jack discusses “viewing the body” of his mother in Surprised by Joy:

“Grief in childhood is complicated with many other mysteries. I was taken into the bedroom where my mother lay dead; as they said, ‘to see her,’ in reality, as I at once knew, ‘to see it.’ There was nothing that a grown-up would call disfigurement – except for that total disfigurement which is death itself. Grief was overwhelmed in terror. To this day I do not know what they mean when they call dead bodies beautiful. The ugliest man alive is an angel compared with the loveliest of the dead. Against all the subsequent paraphernalia of coffin, flowers, hearse, and funeral I reacted with horror…To my hatred for what I already felt to be all the fuss and flummery of the funeral I may perhaps trace something in me which I now recognize as a defect but which I have never fully overcome – a distaste for all that is public, all that belongs to the collective; a boorish inaptitude for formality.” (19-20)

Flora’s academic and spiritual influence is evident. Certainly her loss echoed throughout Jack’s adult life, but the lessons she taught, and the love she gave, made a deep impression on him. We now know where Lewis inherited his penchant for logic!

Now, we will move on to the Lewis patriarch – a compelling and controversial figure – who, I argue, shaped Lewis in various ways. His death also left a lasting impression on his sons, but the death was experienced with a mixture of conflicting emotions.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

ALBERT LEWIS

“I could show you, I think, the very point in St. Albans where, just as I was posting a letter, it occurred to me that when my father said X I despised it, and when any one of my friends said X I thought it was extremely intelligent. It is in our blood; we are furious with our parents before we know it”

– Charles Williams (The Third Inkling – Lindop, 23)

Many biographers believed that Albert Lewis was a pushover who carried his bravado home from the courtroom. Among the traits that the Lewis brothers found repulsive were his tendencies to change information and claim that his version is correct, to eat heavy meals at mid-day (2:30 P.M.), to philosophize loudly, to talk politics to his young sons (now we know the inspiration for Boxen!), to use various catchphrases or “wheezes,” and to strictly control the business of others. He was called a “bully” and a “snob” by some family members. Yet there are positive aspects we recognize in Albert’s character, good and admirable qualities. A promising politician in his youth, Albert had all the markings of a shooting star in the Conservative Party. However his conscience kept him from obtaining such political status. Warnie recalls that Albert would remove people from his office who would “make use of [his] legal knowledge” to “help…commit a swindle”(Lewis Papers, II.65). However noble, Albert’s character continues to be diminished in biographies and academic articles. From where does this less-than-flattering caricature originate? Why Jack himself, in Surprised by Joy:

*”I am sure it is not his fault, I believe much of it was ours; what is certain is that I increasingly found it oppressive to be with him” (SBJ 124-125)

*“You will have grasped that my father was no fool. He even had a streak of genius in him. At the same time he had – when seated in his own arm chair after a heavy midday dinner on an August afternoon with all the windows shut – more power of confusing an issue or taking up a fact wrongly than any man I have ever known. As a result it was impossible to drive into his head any of the realities of our school life, after which (nevertheless) he repeatedly enquired. The first and simplest barrier to communication was that, having earnestly asked, he did not ‘stay for an answer’ or forgot it the moment it was uttered. Some facts must have been asked for and told him, on a moderate computation, once a week, and were received by him each time as perfect novelties. But this was the simplest barrier. Far more often he retained something, but something very unlike what you had said. His mind bubbled over with humor, sentiment, and indignation that, long before he had understood or even listened to your words, some accidental hint had set his imagination to work, he had produced his own version of the facts, and believed that he was getting it from you…What are facts without interpretation?” (ibid, 120-121)

*”I should be worse than a dog if I blamed my lonely father for thus desiring the friendship of his sons; or even if the miserable return I made him did not to this day lie heavy on my conscience…It was extraordinarily tiring. And in my own contributions to these endless talks – which were indeed too adult for me, too anecdotal, too prevailingly jocular – I was increasingly aware of an artificiality. The anecdotes were, indeed, admirable in their kind…But I was acting when I responded to them. Drollery, whimsicality, the kind of humor that borders on the fantastic, was my line. I had to act. My father’s geniality and my own furtive disobediences both helped to drive me into hypocrisy. I could not ‘be myself’ while he was at home. God forgive me, I thought Monday morning, when he went back to his work, the brightest jewel in the week” (ibid, 125-126)

*”At home the real separation and apparent cordiality between my father and myself continued. Every holidays I came back from Kirk with my thoughts and my speech a little clearer, and this made it progressively less possible to have any real conversation with my father. I was far too young and raw to appreciate the other side of the account, to weight the rich (if vague) fertility, the generosity and humor of my father’s mind against the dryness, the rather death-like lucidity, of Kirk’s. With the cruelty of youth I allowed myself to be irritated by traits in my father which, in other elderly men, I have since regarded as lovable foibles. There were so many unbridgeable misunderstandings (ibid, 160-161).

*”Once my brother had left Wyvern and I had gone to it, the classic period of our boyhood was at an end…All began, as I have said, with the fact that our father was out of the house from nine in the morning till six at night. From the very first we build up for ourselves a life that excluded him. He on his part demanded a confidence even more boundless, perhaps, than a father usually, or wisely, demands. One instance of this, early in my life, had far-reaching effects. Once when I was at Oldie’s [Wynyard] and had just begun to try to live as a Christian I wrote out a set of rules for myself and put them in my pocket. On the first day of the holidays, noticing that my pockets bulged with all sorts of papers and that my coat was being pulled out of all shape, he plucked out the whole pile of rubbish and began to go through it. Boylike, I would have died rather than let him see my list of good resolutions. I managed to keep them out of his reach and get them into the fire. I do not see that either of us was to blame; but never from that moment until the hour of his death did I enter his house without first going through my own pockets and removing anything I had wished to keep private. A habit of concealment was thus bred before I had anything guilty to conceal” (emphasis added, Ibid, 119-120)

Indeed, Joan Murphy, a cousin of Jack, spoke about the fact that Albert seemed to suffer from control issues. In a speech to the Oxford C.S. Lewis Society, she stated, “Uncle Al was a very dominant man…[he] was a man who, I think, had no idea how to deal with young people. Uncle Al died in 1929, and that is my first real memory of Jacks…When Uncle Al’s funeral was over, all the family had come. Brothers and aunts from Scotland – the lot – came to our house, because they were all going to go to the boat, and Uncle Bill went out of the room for something and apparently I said, ‘Well, I’m glad that old man is gone because he was horrid,’ I can remember Jacks picking me up and putting me on his knee saying, ‘Out of the mouths of babes and sucklings comes the truth'” (C.S. Lewis and His Circle – White, Wolfe, and Wolfe, 171).

YET, Jack offers us some benefits of living with Albert:

“…I must not leave the reader under the impression that all the happy hours of the holidays occurred during our father’s absence. His temperament was mercurial, his spirits rose as easily as they fell, and his forgiveness was a thorough-going as his displeasure. He was often the most jovial and companionable of parents. He could ‘play the fool’ as well as any of us, and had no regard for his own dignity, ‘conned no state.’ I could not, of course, at that age see what good company (by adult standards) he was, his humor being of the sort that requires at least some knowledge of life for its full appreciation; I merely basked in it as in fine weather” (SBJ, 41)

Long story short: the relationship is rather complicated.

Albert was certainly a heavy presence for young boys, but in truth, he was still crippled by the loss of his wife and worked long hours (sometimes with whiskey) to temper the enduring loneliness. He desperately wished to connect with his sons, but failed in many respects. Sending the boys to public school so soon widened the chasm between father and sons. Albert assumed his sons would simply adopt his ideals, out of respect or obligation. This made him seem insensitive to their various stages of development as individuals, separate from him and his own experience (Albert wished for both of his sons to attend university, but Warnie chose to join military. Albert made condescending statements about this choice for several years). Albert simply wouldn’t adapt to his children, but rather expected them, in their young age and vulnerability, to adapt to him. It appears that Albert struggled to see an event outside of his own perspective. Warnie writes in The Lewis Papers:

“In reading the correspondence which follows, it is easy to see that both his sons must have grown up with an inarticulate resentment against a treatment whose injustice their immaturity prevented them from defining. It was not only that Albert did not understand boys – “he was born old” as his brother in law once said of him – it was that his correspondence forces one to the conclusion that he had not only defined in advance what should be his attitude towards his sons, but had also defined what should be their attitude towards him. Once again we see the clash between the shifting, expanding point of view of youth, and that apparently ineradicable mid-Victorian tendency to regard children not only as static, but actually as a portion – a detached residence as it were – of their parents’ ego” (II. 65 – from the Introduction of “The Pudaita Pie: An Anthology”).

His civic work, which caused him to be away from the family for extended time, was significant indeed. Albert was police court prosecuting solicitor for the Belfast Corporation, but represented a large number of municipal and professional organizations, including the Belfast City Council, the Belfast and County Down Railway, the Belfast Harbour Commissioners, the Post Office, the Ministry of Labour, and the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children.After his death, the Belfast Telegraph published this statement: “The death of Mr. Lewis removed from our midst a strong upright man, a faithful friend, a keen and able advocate, a cultured and educated gentleman, and by his death the city in which his brilliant professional career was spent is appreciatively the poorer” (CL, I, 822)

Why such a division of opinion? Volume 1 of the Collected Letters reveals that Jack kept a secret from his father for years: the fact that he was living with, and helping to support, a divorcee and her daughter.

Let’s briefly return to the emphasized quote from Surprised by Joy mentioned earlier:

“I do not see that either of us was to blame; but never from that moment until the hour of his death did I enter his house without first going through my own pockets and removing anything I had wished to keep private. A habit of concealment was thus bred before I had anything guilty to conceal.”

This, of course, continued without fail when Jack truly did have something to conceal: the fact that he was living with and supporting, a woman and her daughter on his meager income after the war. Jack had trained alongside Paddy Moore at Oxford. Both of Irish descent with similar personalities, the two had become great friends but Paddy would not survive the war; he died at the Battle of Pargny as one of the “first to go” of Jack’s training unit. It is widely known that Jack and Paddy exchanged promises to “look after” the parent of the other if he did not survive. While this is admirable, Jack become rather fixated on Mrs. Moore and even spent furlough with her instead of returning home to see his father. Jack essentially moved in with Paddy’s family and remained that way until Mrs. Moore’s death (The Kilms was jointly purchased by the Moores and Jack). Warnie learned of the domestic arrangement after a visit. Warnie didn’t like Mrs. Moore, but felt that, with the vast difference in their age, there was no possibility for a romantic attachment.

When Warnie wrote to Albert about the “Mrs. Moore business” on 10 May 1920, he seemed confused:

“The Mrs. Moore business is certainly a mystery but I think perhaps you are making too much of it. Have you any idea of the footing on which he is with her? Is she an intellectual? It seems to me preposterous that there can be anything in it. But the whole thing irritates me by its freakishness.”

Albert replies with consternation and concern,

“I confess I do not know what to do or say about Jack’s affair. It worries and depresses me greatly. All I know about the lady is that she is old enough to be his mother – that she is separated from her husband and that she is in poor circumstances. I also know that Jacks has frequently drawn cheques in her favour running up to ₤10 – for what I don’t know. If Jacks were not an impetuous, kind hearted creature who could be cajoled by any woman who has been through the mill, I should not be so uneasy. Then there is the husband whom I have been told is a scoundrel – but the absent are always to blame – some where in the background, who some of these days might try a little amiable black mailing. But outside all these considerations that may be the outcome of a suspicious, police court mind, there is a distraction from work and the folly of the daily letters. Altogether I am uncomfortable.”

For this post, I will not go into details about Mrs. Moore (she already has a Lewis and Women post here), but I wish to underscore that Albert was exceedingly generous during Jack’s young life. Not only did he finance Jack’s personal tutelage with Kirkpatrick, he wrote letters to prominent people in order for Jack to avoid conscription during World War I. Albert also financed the three firsts that Jack eventually achieved. Jack earned a scholarship awarding £80 a term, with tuition costs at £60. In addition, Albert was providing £67 plus expenses. However, Jack was always writing and requesting money. Many of his student letters to his father begin with, “My dear Papy, thank you for the _____________.” Albert was becoming suspicious that so much of Jack’s money was evaporating, and he suspected that Mrs. Moore may be contributing to the problem. Albert had every right to be concerned; he felt that this fly-by-night divorcee was taking advantage of his son. Some of the letters, and the diary, show a rather strange and unorthodox attachment to her, a woman nearly thirty years his senior. Albert was too coy to approach the topic with his son, but he did bring up the constant financial distress which plagued Jack at Oxford. In his diary, Albert wrote, “Wrote Jacks a long letter in reply to one from him asking for an increased allowance: ‘What I [should] know where I am and what I must provide for. If instead of lodging £67 a term to your account I lodged £85 a term to cover everything, would that be sufficient? You must be quite frank with me…” (LP, VIII, 186).

Jack, Maureen, and Mrs. Moore

Jack, Maureen, and Mrs. Moore

Yet even with hesitations about the nature of the relationship , Albert wrote to Mrs. Moore after the death of Paddy to express his condolences:

“Dear Mrs. Moore,

Two days ago, I heard from Jacks that all hope of Paddy’s safety must now be abandoned. I hope I may write of him as ‘Paddy’ for I felt as tho’ I had known him intimately for a long time. I shall not offer you the commonplaces of consolation – about duty and patriotism. When all that is said – and truthfully said – the terrible fact remains – the irremediable loss – the bitter grief. I do however offer you with intense sincerity my true and earnest and deep sympathy and sorrow in your great loss. For all your kindness to my son which I here again ask permission to acknowledge, I am deeply grateful. Believe me, with much sympathy,

your most sincerely,

Albert” (CL, I, 402)

The tension hit a climax on 6 August 1919 while Jack was home. Albert writes in his diary:

“Sitting in the study after dinner I began to talk to Jacks about money matters and the cost of maintaining himself at the University. I asked him if he had any money to his credit, and he said about £15. I happened to go up to the little end room and lying on his table was a piece of paper. I took it up and it proved to be a letter from Cox and Co stating that his a/c was overdrawn by £12 odd. I came down and told him what I had seen. He then admitted that he had told me a lie. As a reason, he said that he had tried to give me his confidence, but I had never given him mine, etc., etc. He referred to incidents of his childhood where I had treated them badly. In further conversation, he said he had no respect for me – nor confidence in me” (CL, I, 461-462)

A month later (6 September), Albert was still stinging from the exchange:

“I have during the past four weeks passed through one of the most miserable periods of my life – in many respect the most miserable. It began with the estrangement from Jacks. On 6 August he deceived me and said terrible, insulting, and despising things to me. God help me! That all my love and devotion and self-sacrifice should have come to this – that ‘he doesn’t respect me. That he doesn’t trust me, and cared for me in a way.’ He has one cause of complaint against me I admit – that I did not visit him while he was in hospital [during wartime convalescence after the Battle of Arras]. I should have sacrificed everything to do so and had he not been comfortable and making good progress I should have done so. The other troubles and anxieties which have come upon me can be faced by courage, endurance, and self-denial. The loss of Jacks’ affection, if it be permanent, is irreparable and leaves me very miserable and heart sore” (CL, I, 402).

In many ways, the rift never fully healed. Jack wrote to Arthur shortly after that stating that Albert “still insists on occupying the position of joint judge, jury, and accuser, while relegating me to that of prisoner at the bar. So long as he refuses to acknowledge any faults on his side or to attribute the whole business to anything but my original sin, I do not see how he can expect a real or permanent reconciliation” (CL, I, 465). In truth, Jack struggled with his inadequacies, perhaps never feeling “good enough” for his father: “I had a curious feeling that my father has ‘given me up’: I feel that he has ceased to ask questions about me as a hopeless enigma. The strain of conversing with him, the hopelessness of trying to make him understand a position, are of course old news: but this time one felt – rather pathetically – that the effort was over for good on his side. I can truly say I am sorry I have contributed so little to his happiness” (AMR – 1922, 106)

Slowly, Albert and Jack began to restore their relationship. Jack still couldn’t quite understand his father, but in between 1922 and 1924, Warnie and Jack began to collect the sayings or “wheezes” uttered by Albert. This shows some appreciation – even if through satire – of their father’s robust personality. Jack tarried for several years grading examination papers while waiting for an opening at Oxford. He attempted to apply for teaching positions at various schools, but each opportunity seemed to dissipate. Jack struggled to keep the household afloat on his small income, subsidized greatly (and secretly) by Albert’s continual support.

Albert supported Jack even after his scholarship expired. Jack completed his final first in English thanks to the generous support of his father. This accomplishment, along with his background in philosophy, helped to earn his spot as a tutor. Albert received a telegram on 20 May 1925 from Jack exclaiming that he was elected as a fellow at Magdalen (and finally financially secure). Albert wrote in his diary: “I went up to his room and burst into tears of joy. I knelt down and thanked God with a full heart. My prayers had been heard and answered” (CL, I, 640).

Young Jack Lewis

In his next letter, Jack gives his heartfelt gratitude to his father for the long, faithful support he had provided, even in the midst of personal speculation and job uncertainty:

“First, let me thank you from the bottom of my heart for the generous support, extended over six years, which alone has enabled me to hang on till this. In this long course, I have seen men at least my equal in ability and qualifications fall out for the lack of it. ‘How can I afford to wait’ was everybody’s question: and few had those at their back who were both able and willing to keep them in the field so long” (CL, I, 642).

Four years later, Jack tended to the bedside of his ailing father, sick with cancer. Albert’s endured treatment and an operation which Jack said he “is taking it like a hero” (CL 819). Jack laments that the “watercloset [toilet] element in his conversation rose from its usual 30% to something nearly like 100%” (CL 808). Jack was doing all of the heavy lifting during Albert’s illness (Warnie was in China on assignment), which caused him great frustration at times. Like when he was a boy, Jack felt like his father was crowding him, desperately trying to win his affection and nurse old wounds while Jack continued to feed his bitter resentments. Jack writes to Warnie, “The patient is rather better…Another thing almost too good to be true is that someone in town advised him, as a cure for rheumatism, to carry a pudaita [“Pudaitabird” was the boys’ nickname for Albert, stemming from his low Irish pronunciation of “potato”] in each pocket – which he actually tried. Oh, and another interesting thing, he was talking as often, about the insolence of Uncle Hamilton [Flora’s brother Augustus] and said, ‘You know, what I don’t like about Gussie is that he never says these desperately insolent things when we’re alone. It’s always to raise a laugh from you boys at my expense.’ I wonder does he regard ‘that fellow Gussie’ as the origin of the whole anti-Pudaita tradition” (CL, I, 817). Albert’s temperature (and temper) fluctuated much to Jack’s dismay. Jack found Little Lea rather suffocating, as he did when he was a young boy under the domestic tyranny of a “bossy” father. Jack was assured that Albert would continue to improve, and left to tend to Oxford business on 21 September 1929. Three days later, Jack received a telegram stating that his father had taken a turn for the worst. Jack immediately began his return journey, but Albert died before he arrived on 25 September of cardiac arrest. Although Jack admits to Barfield that he couldn’t salvage any real love for Albert during his illness (CL 820), Albert’s death leaves an indelible mark on him. The quiet house, the empty rooms devoid of the “booming” voice, the stacks of unread tomes, the tangled garden – all of these attested to the death of the patriarch. Jack wrote to Warnie: “How he filled a room! How hard it was to realise that physically he was not a very big man. our whole world…is either direct or indirect testimony to the same effect. Take away from our conversation all that is imitation and parody (sincerest witness in the world) of his, and how little is left. The way we enjoyed going to Leeborough [Little Lea] and the way we hated it, and the way we enjoyed hating it as you say, one can’t grasp that that is over. And now you could do anything on earth you cared to in the study at midday or on a Sunday, and it is beastly” (CL, I, 827).

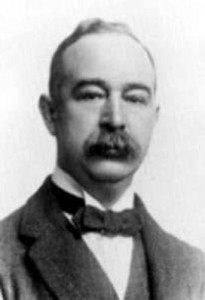

Warnie, Albert, and Jack

While he was making final decisions with his uncles, Jack realizes that maybe he has misunderstood his father all along: “The chief adventure is the quite new light thrown on P. [Pudaitabird] by a closer knowledge of his two brothers. One of his failings – his fussily directed manner… – takes on a new air when one discovers that in his generation the brothers all habitually treated one another in exactly the same way” (CL, I, 846). This is illustrated vividly during a time in which Jack and his uncles chose Albert’s casket:

“Limpopo [Uncle Bill] – and even Limpopo came as a relief in such an atmosphere – put an end to this vulgarity by saying in his deepest bass ‘What’s been used before, huh? There must be some tradition about the thing. What has the custom been in the family, eh?’ And then I suddenly saw, what I’d never seen before: that to them family traditions – the square sheet, the two thirty dinner, the gigantic overcoat – were what school and college traditions are, I don’t say to me, but to most of our generation. It is so simple once you know it. How could it be otherwise in those large Victorian families with their intense vitality, when they had not been to public schools and when the family was actually the solidest institution they experienced? It puts a great many things in a more sympathetic light than I ever saw them in before” (CL, I, 847).

In later years, Jack admitted that he felt horribly about the way he treated his father. He learned to appreciate Albert, all his chuckling and strange habits and rather domineering demeanor. Yet he was a man loved and respected. Jack wanted to please his father; Albert would be pleased with the contribution made by his sons.

George Sayer writes in his biography Jack,

“Albert’s death affected Jack profoundly. He could no longer be in rebellion against the political churchgoing that was part of his father’s way of life. He felt bitterly ashamed of the way he had deceived and denigrated his father in the past, and he determined to do his best to eradicate the weaknesses in his character that had allowed him to do these things. Most importantly, he had a strong feeling that Albert was somehow still alive and helping him. He spoke about this to me and wrote about it to an American correspondent named Vera Matthews. His strong feeling of Albert’s presence created or reinforced in him a belief in personal immortality and also influenced his conduct in times of temptation. These extrasensory experiences helped persuade him to join a Christian church” (133-134)

Jack admits to feeling “humiliation” for treating his father so poorly. Fighting in the war and studying at Oxford taught him that Albert was far superior to “other people’s parents” as Jack wrote. Unfortunately, the lengths that Jack would go to conceal his connection to the Moores put a heavy strain on the father-son relationship. In 1930, Jack admits to Arthur that he had a dream about Albert:

“The most interesting thing since I last wrote is a dream I had about my father…I was in the dining room at Little Lea, with all the gasses lit and talking to my father. I knew perfectly well that he had died, and presently put out my hand and touched him. He felt warm and solid. I said, ‘But of course this body must be only an appearance. You can’t really have a body now.’ He explained that it was only an appearance, and our conversation was cheerful and friendly, but not solemn or emotional, drifted off onto other topics. I then went over to fetch you [Arthur Greeves] and we came across together in a closed car. As we drove I told you of his return in order to prepare you for meeting him: and I think (tho’ this may be a waking intervention) that at that point I was looking forward to seeing him come to the door and say ‘Well Arthur’ and offer you your drink. We were exactly at that place where an increased crushing under the wheels tells you that you have passed off the cinders onto the gravel at the study corner: when you, in a voice of suppressed anxiety, said ‘Oh no, Jack. Its just that you’ve been thinking about him and you’ve imagined he’s there.’ Till that moment everything had been pleasant and homely: but suddenly , as your words made me see the whole adventure from outside, as I realised how it would sound if repeated that I had been TALKING TO A DEAD MAN, the thing wh[ich] had been SO normal in the experiencing it, rose up with such retrospective horror that the nightmare feeling flared up and I woke in terror” (CL, I, 937-938).

Jack had called the mistreatment of his father, the “darkest chapter of my life” (CL, II, 340). When the The Irish Digest wishes to publish paragraphs about Albert titled “My Father’s Eloquent Mistake”(a section included in Surprised by Joy, chapter 2) in 1956, Jack asked to delete a section. “Too like the sin of Ham,” Lewis wrote (CL, III. 681-682). This passage refers to Genesis 9:20-23 in which Ham’s father is naked and the sons refuse to “cover his father’s nakedness.” Thus Jack wishes not to condemn his father and expose all of his flaws to the world. In the end, Jack loved and respected his father, a sensation which he sadly did not experience until after Albert’s death:

“The hard thing is that (after childhood) parents seem usually to be most appreciated when they’re dead. I find so many terms of expression etc of my father’s coming out in me and like it now – I’d have fought against it as long as he was alive” (CL, III, 709-710).

![51Hvj4cOJOL._SX326_BO1,204,203,200_[1]](http://crystalhurd.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/51Hvj4cOJOL._SX326_BO1204203200_1-197x300.jpg)