Flora Lewis

In my last post, I discussed C.S. Lewis’s parents: Albert and Flora. Today, we will examine the role of one particular family member in Jack’s early life – Aunt Lillian “Lily” (Hamilton) Suffern. Lillian Hamilton (1860-1934) was Flora’s older sister and the first child of Thomas and Mary Hamilton. Lily, unlike Flora, was considered a “favorite” child by her parents. She was married to William Suffern. In 1886, William was sent to an asylum in Peebles, Scotland. Later, in 1900, he was declared insane and spent the rest of his life there, dying in 1913 and leaving Lily a widow with no children. Perhaps the most interesting thing about Aunt Lily was her prodigious intellect, which allowed her to wax philosophical on varied subjects. Many people would be surprised to know that Lily was a suffragist, consistently speaking her mind (even if one didn’t care for her opinion). She was known as rather cantankerous. She moved several times after her husband’s death, and was incredibly fond of her nephew Jack, whom she called “Cleeve.” Aunt Lily was something of a character; while she spoke out against women’s rights (including birth control) and animal rights, she never hesitated to cross anyone who dared to contradict her. In the letters and diary, Jack discusses how smart and engaging she was. Warren provides a portrait of her in Volume 2 of The Lewis Papers, included with the following description:

“Lily was a clever, but eccentric woman, handsome in her youth. Her cutting insolence and her extremely quarrelsome disposition made her the stormy petrel of the family, with all or several of whose members she was perpetually at war. Albert [Lewis] never forgave her for the arrow she launched at him in writing to another member of the clan on a legal problem, when she observed of him in an airy parenthesis, ‘for poor Allie is so ignorant.’ The good nature of her nephew Clive Lewis…enabled her for many years in later life to conduct a pseudo-metaphysical correspondence which bears melancholy evidence of a good brain run to seed” (AMR 471). Jack writes that Aunt Lily “talked all the time, with her usual even, interminable fluency, on a variety of subjects. Her conversation is like an old drawer, full of both rubbish and valuable things, but all thrown together in great disorder” (CL, I, 127).

Jack continues, “She has been here for about three days and has snubbed a bookseller in Oxford, written to the local paper, crossed swords with the Vicar’s wife, and started a quarrel with her landlord” (AMR 127).

Indeed, Aunt Lily didn’t mind to get in a scuff with any clergyman nor did she attend church, despite the fact that she grew up the daughter of Reverend Hamilton: “Being asked why, she said she had vowed never to enter any church until the clergy as a body came out in defense of the Dog’s Protection Bill. ‘Oh!’ said the priest’s wife in horrified amazement. ‘So you object to vivisection?’ ‘I object to all infamies,’ replied Aunt L. Nevertheless the Vicar and the wife came to her all humble at the journey’s end and said, ‘Even if you don’t come to church, will you come to our whist drive?’ She says all parsons look like scolded dogs when you challenge them on this subject” (CL, I, 127).

Title page for Spirits in Bondage – 1919

Jack also found Aunt Lily a fine judge of literary works. He often shared drafts of works in progress with her. After publishing his poetry collection Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics, Jack writes that Aunt Lily “put several people on” to it, “recording many nice things said” (AMR 21). However, she had strong opinions about Jack’s drafts of Dymer: “She strongly disapproved of ‘Dymer’ which I had left with her last week. She called it brutal. She said, ‘Where has all your old simplicity and rightness of language gone?’ She said I seemed to be deliberately slipshod and wrong in my words…She also said I ‘must not describe.’ When she came to a description of a wood in a poem – whether in Keats or me!! – she gave it up. She didn’t mind a man writing a poem just about a wood: but to have a wood flung in your way when you were reading about a man – !…I asked her if she disliked Dymer himself: she said, no, it was me: Dymer was just a young animal let loose” (AMR 132).

Jack continued to take poetic criticism from Lily, who adored poet Robert Browning: “The coarseness of ‘Dymer’ depended apparently on the word ‘wenched’ in the first canto. She took this very seriously: excused me on the ground of having no mother or sisters and because Oxford men were notoriously coarse – coarser than those of Cambridge. I reminded her that it was the Cambridge undergraduates who had torn down the gates of women’s colleges and jeered at them. She replied without hesitation, ‘The young men are quite right to defend themselves.’ She then told me a very disgusting story of two medical students here in Oxford, who she had seen dragging off a dog into the laboratories: and they were laughing together as they talked of the old man who had sold it making them promise to give it a good home and be kind to it. After that, I no longer defended Oxford again not ever shall” (AMR 143).

A copy of Dymer. Like Spirits in Bondage, it was published under the pseudonym Clive Hamilton

Lily and Jack often exchanged their work. Jack read an essay by Aunt Lily in 1922 and “thought it was great literature.” He continues, “You can see at any rate that she’s a real, convinced prophet and not a bit of a quack. Her absolute inability to take in anything that cannot be used as fuel for her own particular fire is also a prophet’s characteristic fault” (AMR 131).

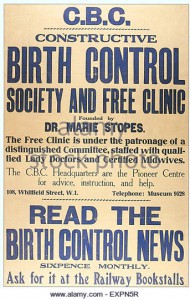

Aunt Lily, as a suffragist, fought tirelessly for women’s rights, including reproductive rights. In one story Jack recalls in his diary, Aunt Lily argues with a woman over her children and then vows to distribute “leaflets issued by the C.B.C. (Constructive Birth Control”:

Dr. Marie Stopes was called an “early sex reformer who devoted herself to birth control” (CL 557).

Jack makes a passing (and rather comical) reference to her in a letter to Warnie on 1 July 1921

“There was one inexplicable anecdote. She had been held up by a crush of prams at Carfax and had asked one obstructive woman to take her pram off the pavement. The woman replied that she had a right to be there. Aunt Lily retorted that she had no right to bring these children into the world for other people to look after and still less to block up the pavement. The woman said she was shopping. Aunt Lily said it was bad for the child to be taken shopping and the only good thing was that it killed some of them off.

“I asked her why on earth she said such a thing. ‘I was angry,’ she answered. I replied, quoting Plato, that anger was an aggravation, not an excuse. She added that she had a lot of leaflets issued by the C.B.C. (Constructive Birth Control): and she was going to drop one into every pram the next time she went into Oxford” (emphasis added, AMR 153).

“Pram” = baby carriage

Additionally, Aunt Lily, speaking of a wife who had left a bad husband, claimed, “Her consolation is that she stopped a bad heredity from perpetuating itself: her strain and her bringing up has made good the children, so that particular man is done with – biologically” (AMR 131-132).

Due to Lily’s frequent moves, Jack had to often find her new residence. On a bus ride to her new cottage, he gave the bus driver her address: ‘The conductor did not at once understand where I wanted to stop, and a white bearded old farmer chipped in, ‘You now, Jarge – where that old gal lives along of all them cats.’ I explained that this was exactly where I did want to go. My informant remarked, ‘You’ll ‘ave a job to get in when you DO get there.’ He was as good as his word, for when I reached the cottage I found the fence supporting a wire structure about nine feet high which was continued even over the gate. She does it to prevent her cats escaping into the main road” (CL, I, 626-627).

Interestingly enough, Aunt Lily often told Jack family stories. Jack admitted to her that the reason he wished to finish his degree in English in one year (as opposed to three) was to save his father’s expenses, as Jack’s scholarship had expired (as noted in my last post, Jack’s budget, coupled with his strange living arrangement, was a cause of disagreement with his father): “I remarked, in answer to some question, how rushed I had been by the shortened time in wh[ich] I had taken this School. She said, ‘Why did you?’ and that it wasn’t fair either to my father or myself, who had nothing to do with his money and only wanted to keep me there. I said that, on the contrary, he wanted to retire: she said that W and I had been provided for and my father had been in a position to retire long ago before my mother’s death but she (my mother) had persuaded him to continue his police court work and make more. Who knows?” (AMR 246)

Jack continued to visit Aunt Suffern when his studies and domestic responsibilities permitted it. It is important to note that Aunt Lily never visited Jack at his home, and was thus ignorant of the living arrangement he had with Mrs. Moore. Perhaps Jack felt that in his aunt he could recover a small piece of his mother.

Aunt Lily died in 1934.