Week Eight of the C.S. Lewis and Women Series

Portrayals in The Pilgrim’s Regress

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.com

This week, we will begin a literary exploration of Lewis’s female characters. Lewis’s first fictional prose text was titled The Pilgrim’s Regress, published in 1933. The story is an allegory of John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, in which John, the protagonist, is fascinated by an “island” and endures a philosophical maze, fights a dragon, and stumbles upon a new realization about himself, humanity, and “The Landlord”.

There are four main female figures in the book which I will outline today. PLEASE understand that this is allegory, therefore, the characters are essentially symbols. In this work, Lewis does not patronize women (Lewis would have never been foolish enough to operate on such shallow generalities), rather, he utilizes feminine characters as representative of an overarching concept. For example, Walter Hooper tells us in C.S. Lewis: A Companion and Guide that Mother Kirk actually symbolizes “Traditional Christianity”. If Lewis casts a female character in an unflattering light, he is not criticizing her specifically, rather he is criticizing the idea(s) which she represents. In the beginning of the book, John sees a vision of an island, an image which inspires much delight and curiosity. John then spends his life chasing the island, seeking an avenue to lead him back to his cherished vision. Throughout this narrative (which Hooper categorizes as “autobiographical”), John strives to reach the island, but is told by various individuals that the island is a mirage and doesn’t exist at all or that it is a misplaced desire for sex. Although John is strongly persuaded at times, eventually he perseveres and finds contentment, but only after he relinquishes the perceived power over his own life. Cumulatively, the women in this story are typically positive characters. Most of the religiously ambivalent characters are, in fact, male characters.

Let’s briefly explore the four female characters (one which is included in a larger group) John encounters on his journey, which intentionally parallels Lewis’s own conversion experience:

Brown Girl(s) & Media Halfways

“It was me you wanted…I am better than your silly Islands”

In Chapter four of Book One, in a section appropriately titled “Leah for Rachel”, John peers out a window in the wall in search of the island. Eventually, John gains the courage to explore the forest, but all the while he is questioning its existence and considering that the island could be “a feeling” instead of a reality. Then John is stirred from contemplation when he hears a voice. Lewis writes, “It was quite close at hand and very sweet, and not at all like the old voice of the wood. When he looked round he saw what he had never expected, yet he was not surprised. There in the grass beside him sat a laughing brown girl of about his own age, and she had no clothes on. ‘It was me you wanted,’ said the brown girl. ‘I am better than your silly Islands.’ And John rose and caught her, all in haste, and committed fornication with her in the wood” (16).

John begins a long tryst with the “brown girls” but is surprised to find himself still unsatisfied. After time, John begins to loathe her, as she comes to represent his unfulfilled desire and unrelenting frustration:

The girl was still there and the appearance of her was hateful to John: and he saw that she knew this, and the more she knew it the more she stared at him, smiling. He looked round and saw how small the wood was after all – a beggarly strip of trees between the road and a field that he knew well. Nowhere in sight was there anything that he liked at all. ‘I shall not come back here,’ said John. ‘What I wanted is not here. It wasn’t you I wanted, you know.’

John is soon a slave to his own pleasures. He is haunted by the “brown girl” and the “children” they bore. They appear everywhere, visible only to him. He is continually tormented by their presence. As he creeps off to bed after a hard day, he finds the brown girl inescapable and has “no spirit to resist her blandishments” (17). Later, in Book Two, Chapter Three, John meets an intriguing woman who is “young and comely, through a little dark of complexion” (25). She is also “friendly and not frank, but not wanton like the brown girls” (25). Her name is Media Halfways. In the next chapter, John and Media are walking through the lane, listening to the enchanting bells of the city. John is moved by the music and soon, John and Media become more affectionate:

As they went on they walked closer, and soon they were walking arm and arm. Then they kissed each other: and after that they went on their way kissing and talking in slow voices, of sad and beautiful things. And the shadow of the wood and the sweetness of the girl and the sleepy sound of the bells reminded John a little bit of the Island, and a little bit of the brown girls. ‘This is what I have been looking for all my life,’ said John. ‘The brown girls were too gross and the Island was too fine. This is the real thing.’ ‘This is Love,’ said Media with a deep sigh. ‘This is the way to the real Island’.

Media’s father, Mr. Halfways, sings and plays the harp for John. In musical rapture, John is swept up in a vision of the island, and begs for Mr. Halfways to repeat the song. Mr. Halfways, doubtful of the Island’s existence, tells John that he is found the island “in one another’s hearts”. However, the infatuation is short-lived. Media’s brother, Gus Halfway, interrupts the lovers’ conversation: “Well, Brownie, at your tricks again?” Media flees the room, telling John, “All is over. Our dream – is shattered. Our mystery – is profaned. I would have taught you all the secrets of love, and now you are lost to me forever. We must part.” Gus then reveals that his sister is a “brown girl” and that his father has “been in the pay of the Brownies all his life. He doesn’t know it, the old chucklehead. Calls them the Muses, or the Spirit, or some rot. In actual fact, he is by profession a pimp” (29). Gus then proceeds to persuade John that science is the new “Island”. He states, “Our fathers made images of what they called gods and goddesses; but they were really only brown girls and brown boys whitewashed – as anyone found out by looking at them too long. All self-deception and phallic sentiment. But here you have the real art. Nothing erotic about her, eh?” [points to his bus].

As most can contrive, the brown girls represent LUST. They are poor substitutes for John’s Island (hence the Old Testament reference “Leah for Rachel”). John ultimately transforms his desire for the (intangible) Island into sexual gratification and longing. However, the fix is only temporary, leaving John confused and irritated that his philosophical itch remains unscratched. Why do the brown girls leave him so empty?

It is also important to note that Lewis is NOT patronizing dark-skinned women. This is not Lewis’s reiteration of the “Eve” or “temptress” complex. If this were so, John would be written as more the victim of the vicious brown girls. John is illustrating a young man’s insatiable lust, which leads him to fornicate. John is not a victim, he is a co-conspirator. He is morally culpable for his behavior. Metaphorically the brown girls are no more than a perceived facsimile, John’s failed attempt to discover the Island.

By employing the color brown, Lewis is noting the condition of the brown girls’ souls – brown representing a faint hue of darkness. This is reflected in a conversation John has with his friend and travelling companion Vertue:

John: “There was a great deal to be said for Media after all…It is true she had a dark complexion. And yet – is not brown as necessary to the spectrum as any other colour?”

Vertue: “Is not every colour equally a corruption of the white radiance?”

John: “What we call evil – our greatest weaknesses – seen in the true setting is an element in the good. I am the doubter and the doubt.

Vertue: “What we call our righteousness is filthy rags.” (105)

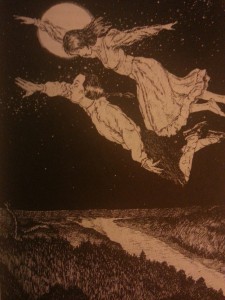

Contemplation (Daughter of Wisdom)

Although she makes a brief appearance, Contemplation’s key role is to assist John as he travels toward his ultimate destination. In Book Seven, she wakes John up and beckons him to continue his travels. When they reach a crevasse, she inspires him to jump. John “felt no doubt of her” and leapt. Instead of landing, John flies with Contemplation to the top of the mountain. Contemplation travels with him and states that when he “learned to fly further, we can leap fro here right into the Island” (92). When he awakes the next morning, Contemplation is absent. Later, in Book Nine, Contemplation returns to lead John through the darkness to the castle gates. John claims that she is a different Contemplation, to which she replies that the former Lady was ” one of my shadows whom you have met” (124). Contemplation leads John through heavy rain and across a dark sea. When he struggles to release her grip, John finds that he has been dreaming and wakes up back in the cave. Contemplation is a guide, but she does not, like so many of the male characters, crowd John with her philosophy/theology. On the contrary, she guides him to search deeper for meaning and fulfillment.

Mother Kirk

“‘The art of diving is not to do anything new but simply to cease doing something. you have only to let yourself go”

As Walter Hooper mentioned, Mother Kirk represents Traditional Christianity. John and Vertue first meet Mother Kirk as they plan to scale the mountain. Her dress is tattered and John’s first instinct is to consider her insane. Mother Kirk offers to carry the men up, but as it is late, Mother Kirk invites them to her home. There she tells a modified version of “The Fall”, a dark narrative in which the Landlord is forced to evict a “tenant” due to disobedience. Then the spurned individual enticed others to stray, including the wife of a young couple. The evil entity persuades the farmer’s wife to eat a nice mountain-apple, and a large canyon formed in the land. It’s name –Peccatum Adae (Sin of Adam). John, still intrigued by the idea of the Landlord, inquires further about the rules established by the Landlord. Mother Kirk replies, “For one thing, the taste created such a craving in the man and the woman that they thought they could never eat enough of it; and they were not content with all the wild apple trees, but planted more and more, and grafted mountain-apple on to every other kind of tree so that every fruit should have a dash of that taste in it. they succeeded so well that they whole vegetable system of the country is now infected…” Later Mother Kirk claims she will carry the men down in the morning, but they must strictly follow her instructions. John replies,

“I am afraid it is no use, mother…I cannot put myself under anyone’s orders. I must be the captain of my soul and the master of my fate” (60).

This represents Lewis’s refusal to surrender to Christian principles. He is told what path is best, but refuses to acknowledge it. He is told by others that Mother Kirk was respected, but was regrettably out of date. By his own volition, John chooses the long and complicated journey to arrive back with Mother Kirk. This time, she informs him that he must surrender to reach the Island: “It is only necessary…to abandon all efforts at self-preservation” (128). John undergoes a baptismal scene (similar to what Eustace experiences in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader). He hears the voices of others, discouraging him from diving in. But at last the moment of decision had been reached: “And with that he took a header into the pool and they saw him no more. And how John managed it or what he felt I did not know, but he also rubbed his hands, shut his eyes, despaired, and let himself go. It was not a good dive, but, at least, he reached the water head first” (129).

Here, even in Lewis’s first work, we see that women are playing a variety of roles. They are not demonized, nor are they portrayed as saints (a literary characteristic of which Lewis is often accused). His women are dimensional, beautiful, but most importantly, authentic. From the sin and squalor of the “brown girls” to the reverence inspired by Mother Kirk, John’s journey explores the complicated journey of faith and the characters present in our narratives.

Next week, we will tackle the collection of stories which have, single-handedly, contributed to the perception of Lewis’s “misogyny”. However, I will illustrate that Lewis crafts several complex and beautiful female characters who inhabit a magical land only entered by a wardrobe. One neglected scene from The Horse and His Boy will give us great insight into Lewis’s complicated, but unprejudiced perspective of women.

The Chronicles of Narnia will be discussed next week. Join me!

![Pilgrimsregress[1]](http://crystalhurd.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Pilgrimsregress1-193x300.jpg)

Comments

I read that book a couple decades ago, but you’ve brought the characters back to mind vividly for me, Crystal. What do you think of one of the minor female characters, the one who does that rather odd, jerky dance and then complains ( when criticized) that all great artists are misunderstood?