This talk is adapted from a lecture on Lewis’s Narrative Poems for Northwind Theological Seminary’s program in Romantic Theology and Inklings Studies during the winter of 2021. I currently serve as Visiting Faculty for this wonderful program. For more information on how you can earn a master’s or doctorate in Romantic Theology, visit the Northwind site: https://www.northwindseminary.org/romantic-theology-degree

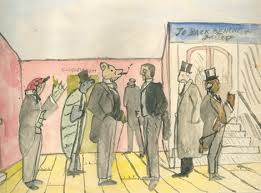

C. S. Lewis’s development as a writer has a long and varied history. His first stories involved anthropomorphic characters from Animal-Land, known collectively as Boxen. These stories feature Lord Big, a character that Lewis later reflected bore a strong resemblance to Churchill. Imbued with an uncanny knowledge of local politics most likely influenced by Albert’s domestic conversations, Boxen illustrates the imaginative prowess of both Lewis boys.

Due to the Irish damp, Jack Lewis was often kept inside. This led to an exploration of his father’s bookshelves and, once the family was established at Little Lea, an attic space that young Jack claimed as an “office.” The world seemed to bound to expand off of the page. Warnie wrote a Boxonian journal. Jack constructed a map for the world. The few fragments of story and illustration survive in Boxen: Childhood Chronicles Before Narnia co-authored with Warnie.

Here lies Jack’s first attempt to tackle adult issues in childhood narrative form, a skill that would become quite valuable when he would pen his Narnian Chronicles decades later. Some of the stories involving Lord Big are quite sophisticated for a young man to be exploring. Perhaps this is Jack’s precociousness, but equal credit should be given to Albert for introducing (despite his sons’ ire) mature conversations about the social and political swirl of Belfast. Although his sons hated to hear remnants of Albert’s day at Little Lea, it cannot be denied that Albert’s introduction gave his sons a proper perspective on understanding two sides of an argument and also the complexities of compromise. This would assist Lewis in writing some of his greatest works (like Narnia) and provide Warnie with an intimate knowledge of politics that he would capture later in his French history works.

And yet, Lord Big was a hero, Dymer more of a villain.

Lewis was an early admirer of poetry, citing poetry as a driving influence in his search for Joy, namely through Longfellow’s translation of Saga of King Olaf and Tegner’s Drapa (the unrhymed translation, no less). It was there that a young Jack Lewis’s imagination grasped the immense sorrow of Balder’s death, of a voice lifted clear against a pale sky in the northern regions which would haunt him the rest of his life. Even though he was unfamiliar with the Norse myth at the time (“I knew nothing of Balder”), Jack was immediately transformed.

Thus soon after, Jack Lewis began to write poetry. Early attempts at poetry survive in the Family Papers, although most are included in Don King’s The Collected Poems of C. S. Lewis: A Critical Edition. Walter Hooper cites several early drafts of poems such as a poem inspired by Nibelung’s Ring (1912), Loki Bound, Metrical Meditations of a Cod (later known as Spirits in Bondage), The Quest for Bleheris (now published in Volume 14 of Sehnsucht: The C.S. Lewis Journal – 2021) and Medea’s Childhood. All of these were written before Lewis’s entrance to Oxford University (Hooper viii). In the introduction to Narrative Poems, Hooper also mentions other poetic fragments such as Wild Hunt, Foster, Helen, and Sigrid.

Lewis struggled to become a poet in his youth, finally publishing Spirits in Bondage: A Cycle of Lyrics after the First World War. It is important to note that the Lewis we meet in Spirits in Bondage is a far cry from the one we admire in Mere Christianity. Early Lewis is hardened, bitter, disenfranchised. He seems, despite his towering intellect, to be a total disaffected and jaded snob. He has long since discarded his robes of religion, a deep ambivalence that Albert and Warnie detected in Jack’s first poetry collection.

Dymer started out as prose and was later adapted in rhyme royal (ABABBCC rhyme scheme) with nine cantos. Strangely enough, Lewis’s final work of fiction, Till We Have Faces, began its life as a poem, later abandoned in verse if not in concept. If Spirits in Bondage was meant to be autobiographical, so would, to an extent, his next published poetry collection–a long narrative poem called Dymer. Published in 1926, Dymer was written over a period of several years. The idea had festered in his mind for that time, during Lewis’s time at Oxford as a student. J.M. Dent offered the young poet an acceptable amount for the text, which was presented under the pseudonym Clive Hamilton (his first name and mother’s maiden name). During the period of 1922-1925, Lewis worked almost daily on the poem, discussing it generously in his diary All My Road Before Me.

Lewis signed his contract for Dymer on March 25, 1926. According to the agreement, Lewis was to receive 10 percent royalties on copies sold outside the U.S.A., 12.5 percent “on the second thousand copies sold,” 15 percent on all copies over 2,000. If any copies were sold in the U.S., Lewis was to receive 10 percent of the American royalties. Included in the contract was the possibility of “two [additional] books of poems on the same terms as those set forth in this agreement.” The bottom right corner bears Lewis’s signature.

However, despite some positive reviews, Dymer’s sales were dismal. For one, modern poetry–spearheaded by the likes of T. S. Eliot–was gaining momentum in literature and culture. Old poetic traditions were being discarded, rhymes ignored, iambs abandoned. Suddenly, “a patient etherized on a table” was good poetry. Jack had missed the boat. Dymer was an echo of the old era. Jack would later declare himself a dinosaur in “De Descriptione Temporum,” his inaugural address at Cambridge. He replied to one correspondent that he couldn’t rightly judge the present when his back was always to the engine.

Dymer captures the angst of a young man born in The Perfect City. Here, all aspects of life are regulated. Dymer peers out of the window during school and becomes enchanted by the melody of a songbird. Frustrated, Dymer approaches and assaults his lecturer, killing him instantly while the other students look on in horror. Dymer then leaves the city, sheds his clothes (a metaphorical Adam), and heads for the woods where the wild, untamed wilderness awaits him. It is fascinating to note that Dymer’s name was changed at one point to Ask, as in Ask and Embla (the “Adam and Eve” of Norse mythology). In the forest, Dymer finds a luxurious wardrobe (with a mirror) and clothes himself while partaking in a mysterious feast laid out for him. He enters a mansion and meets a strange woman, beds her, and awakens in the morning. His lover is gone; he has forgotten, in all of his selfish reveling, to ask her name. He exits the palace to meet the morning and discovers that, upon his return to the palace, all entrances are barred by an old she-monster/hag. He threatens to move her, but he finds himself limping out later. As a rainstorm begins, Dymer wanders in the forest until he meets a wounded man. This man explains to Dymer that he had unknowingly started a great revolution in the City: “… Once the lying spirit of a cause / with maddening words dethrones the mind of men, / They’re past the reach of prayer” (IV. 29). Many were killed and wounded. Dymer is frightened to know that these atrocities are being done in his name.

“And we had firebrands too. Tower after tower / Fell sheathed in thundering flame / The street was like / a furnace mouth. We had them in our power! / Then was the time to mock them and to strike, / To flay men and spit women on the pike, / Bidding them dance. Wherever the most shame / was done the doer called in Dymer’s name” (IV.30)

The man, not realizing that he is talking to Dymer, states that he wish he could kill Dymer for the trouble he has caused in the city. Soon after, the man dies, and Dymer begins to understand the domino effect of his one foul decision on the City at large. A totalitarian leader named Bran rises up as part of the rebellion. His leadership, we are led to believe, is just as corrupt as the previous leadership in The Perfect City. He turns on his soldiers and scares all of them who dare to defy him.

“Pack up the dreams and let the life begin”

“…how soon it all ran out! And I suppose / They up there, the old contriving powers, / They knew it all the time–for someone knows / And waits and watches till we pluck the flowers, / Then leaps. So soon–my store of happy hours / All gone before I knew. I have expended / My whole wealth in a day. it’s finished, ended.

And nothing left. Can it be possible / that joy flows through and when the course is run, / It leaves no change, no mark on us to tell / its passing? And as poor as we’ve begun / We end the richest day? What we have won, / Can it all die like this?…Joy flickers on / the razor-edge of the present and is gone” (V.9, 10).

Dymer nearly falls from a cliff, but he is awoken to a new life in Canto VI stating, “I’ll babble now / No longer…I’m broken in. Pack up the dreams and let the life begin'” (VI. 2).

Dymer hears the report of gunfire and finds a man shooting a songbird (the same kind that enchanted Dymer in the classroom): “They sing from dawn till dark, / and interrupt my dreams too long,” the man replies (VI.9). The man is called The Master, who has built his land up to protect his “dream state.” The Master destroys anything that disrupts his dreams. Dymer informs The Master about his lover and claims that “she was no dream.” But he soon realizes that his recall has been drenched in desire: “‘But every part / Was what I made it–all that I had dreamed– / No more, no less” (VII.20). In dreams, men have all that they desire, no difficulties, no scorn or criticism. Yet dreams can return to us the dust of long buried sins. Dymer realizes that dreams are only temporary joy; ultimately dreams and terror are mingled. Can we not remember Eden without the tang of forbidden fruit, the shame of our nakedness? Dymer understands that his dreams of joy have been immature fancies, and real life is a sober awakening.

“That I was making everything I saw, / Too sweet, far too well fitted to desire / To be a living thing? Those forests draw / No sap from the kind earth: the solar fire / And soft rain feed them not: that fairy brier / Pricks not: the birds sing sweetly in that brake / Not for their own delight but for my sake! “(VII.8)

Dymer recalls to the Master his experience with his lover, stating “her sweetness drew a veil before my eyes” (VII.21). Yet his desire for her is simply a selfish desire. He speaks of her as though she had fooled him into believing the dream, blaming her like Adam blamed Eve in the Garden of Eden:

She said, for this land only did men love / The shadow-lands of earth. All our disease / Of longing, all the hopes we fabled of, / Fortunate islands or Hesperian seas / Of woods beyond the West, were but the breeze / They blew from off the shore: one far, spent breath / That reached even to the world of change and death. ‘ She told me I had journeyed home at last / Into the golden age and the good countrie / That had been always there. She bade me cast / My cares behind forever: –on her knee / worshipped me, lord and love — oh, I can see / Her red lips even now! Is it not wrong / That men’s delusions should be made so strong?” (VII.22-23).

The Master turns on Dymer for admitting his dream was farcical. This revelation is a threat to all the Master has been attempting to preserve: a state of pure bliss devoid of pain, harm, and compromise. Angered, the Master raises his gun, and Dymer runs for his life.

“You should have asked my name”

In Canto VIII, Dymer finally reunites with his lover, but she is cold and distant: “You should have asked my name,” she states. Dymer then realizes that she is, like the snake in the Garden, a hidden form of the gods who has come to fool Dymer. He feels betrayed, cheated. “You came in human shape, in sweet disguises / Wooing me, lurking for me in my path, / Hid your eternal cold and with woman’s eyes, / Snared me with shows of love — and all was lies” (VIII. 13).

“Must things of dust / Guess their own way in the dark?” She said, “They must.” (VIII.12).

Dymer cries, speaking to the gods (and echoing Jesus), “Why hast Thou forsaken me? / Was there no world at all, but only I / Dreaming of gods and men?” (IX.5) A sentry appears right before Dymer discovers that he has fathered a beast with his lover. Borrowing the sentry’s armor and spear, Dymer fights the beast. Dymer is slain. The sun rises. Around his body bloom flowers, and the beast/son transforms into a god “towering large against the skies / A wing’d and sworded shape, whose foam-like hair / lay white about its shoulders, and the air / That came from it was burning hot” (IX. 34).

Analysis

Dymer is relatively obscure in the vast bibliography of C. S. Lewis. Most of his fame, of course, derives from his post-conversion apologetic works (of which I include The Chronicles of Narnia). Certainly, Lewis’s Christian writings is what he is remembered for, yet there are kernels of our beloved Lewis in this early and frustrated atheist. Many of the ideas that later bloomed into stories are here, if in “seed” form, just awaiting the moment to bloom. In his 1950 preface, Lewis writes that Dymer is “an extreme anarchist.” He continues to state that he “put into it my hatred of my public school and my recent hatred of the army. But I was already critical of my own anarchism” (3)

Lewis writes that his hero was a man “escaping from illusion.”

He begins by egregiously supposing the universe to be his friend and seems for a time to fine confirmation of his belief. Then he tries, as we all try, to repeat his moment of youth rapture. it cannot be done; the old Matriarch sees to that. On top of his rebuff comes the discovery of the consequences which his rebellion against the City has produced. He sinks into despair and gives utterance to the pessimism which had on the whole, been my own view about six years earlier. Hunger and a shock of real danger bring him to his sense and he at last accepts reality. But just as he is setting out on the new and soberer life, the shabbiest of all brides is offered to him; the false promise that by magic or invited illusion there may be a short cut back to the one happiness he remembers. He relapses and swallows the bait, but he has grown too mature to be really deceived. He finds that wish-fulfilment dream leads to the fear-fulfilment dream, recovers himself, defies the Magician who tempted him, and faces his destiny. (5-6)

I wish to examine a few aspects of Dymer which are echoed in one of Lewis’s later works.

Till We Have Faces

Dymer and Lewis’s last (and self-declared best) work of fiction have several things in common. Dymer is “wooed” by the pantheistic call of nature into a mansion where he takes a lover. The atmosphere is both “holy and unholy.” The lover, we learn later, is a shape made by the gods to fool Dymer. Until Canto IX, Dymer does not know the identity of his lover. His belief in her and the dreams she inspires enchant him, but lures him away from TRUTH.

In Till We Have Faces, Psyche is wooed by Cupid to his secret mansion as a married coupling. Psyche knows his name, but is forbidden to see him. Both Dymer and Psyche must meet in the dark. Yet, Psyche’s belief in her lover makes her stronger, wiser. It is her sister Orual’s unbelief that is Psyche’s undoing, more specifically, her sister’s selfish desire to possess her. Like Dymer, Orual will only have her sister on her terms, thus she calls Psyche’s reality a farce. Notice that young Jack uses the term “veil” twice in describing the dream to the Master. He felt that his lover deceived him by drawing a “veil” over his face. Symbolically, this is to avoid facing the truth of his dream state, as Orual wears a veil to hid her physical and spiritual “ugliness.”

Much of Lewis’s work revolves around the theme of uncovering the truth about ourselves. Characters struggle with masks, with identity crises. And each time, it is intense self-reflection that the character requires to grow. Consider Mark and Jane Studdock from That Hideous Strength. Both spouses must discard their social notions of husband and wife, but learn to consider each other and rid themselves of vanity and selfishness. Only then can true harmony be achieved. It is the “drowsy half-waking” of forgetting ourselves that provides us with unrelenting joy, a joy that cannot be replicated or stolen or facsimiled by the shallow world.

It isn’t that your dreams are broken and shattered; it is that your life surrendered to Christ is far more adventurous than the one you ever intended. Chasing joy and discovering Joy. HIS reality > your dreams

Lewis mentions here the term “shadow-lands,” a term used to represent a passing from “reality” to “dreams”; yet his meaning from The Chronicles of Narnia is the reverse: a passing from dreams dark and tainted to a reality unlike anything our minds can fathom.

There is so much more to explore here, but I will defer to Jerry Root’s fantastic annotated edition of Dymer: Splendour in the Dark: C. S. Lewis’s Dymer in His Life and Work. This work not only explores Dymer as a stand-alone poem, but situates it in context with the rest of Lewis’s life and work. As a poem, it is fascinating and brilliant; as Jack’s first published “story” (in poetic form), it is brimming with insights and future glimpses into Lewis’s literary journey.